72.1.285

Woman Combing her Hair

1801 – 1804 (Date created)

Color woodcut on paper

10.438 in W x 15.25 in H(Paper)

Japanese

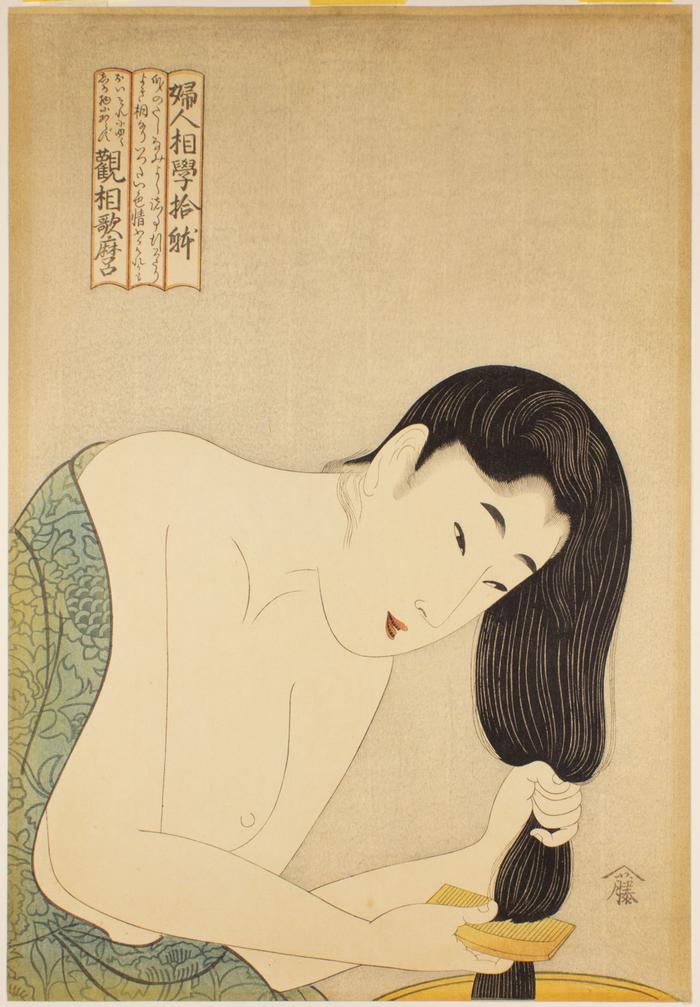

This oban-sized nishiki-e woodblock print portrays the bust of a single female figure combing her hair. Her body emerges from the lower left corner of the composition, occupying the center of the print, and serving as the central focus of the image. Placed against the empty space of the print’s top-right corner, the figure balances the image and creates a dynamic asymmetrical composition. The soft, parchment-colored page provides the flesh for the figure, and also draws the viewer’s gaze towards the figure's dark hair and the blue kimono draped over her semi-nude frame. To the right side of the print are the woman’s hair, comb, and washbasin. She combs her hair in the same vein as the female figure depicted in Tokuriki Tomikichirō’s 1947 woodblock print held in the University Library System collection, titled Woman Combing Her Hair, exemplifying the omnipresence of such beauty rituals across the history of modern Japanese art.

Two other less obvious beauty standards are also present in this work. The first of these is the blackening of the figure’s teeth, known as ohaguro. This time-honored tradition not only protected against tooth decay but also allowed married women to signify their beauty, health, and aristocratic status. The second, lesser-known beauty standard depicted in Kami-suki is hikimayu, or the removal of natural eyebrows in favor of drawn-on reproductions, often performed in order to make the application of white makeup (known as oshiroi) more convenient.

Shifting one’s attention away from the female figure, one can see that in the upper left corner of the print is a three-leaved cartouche containing information on the work's publisher and artist, Kitagawa Utamaro. The furthest-right portion of the cartouche offers the series title in which Kami-suki is a portion, Ten Types in the Physiognomic Study of Women (fujin sogaku jittai [婦人相学拾躰]) which was created between 1801 and 1804.[1] This group of works is frequently discussed in comparison with two incomplete series designed by Utamaro between 1792 and 1793: Ten Types in the Physiognomic Study of Women (fujin sogaku juttai [婦人相学十躰]), and Ten Classes of Women's Physiognomy (fujo ninso juppo [婦女人相十品]) .[2] Through each of these series, Utamaro hoped to display a variety of female “types” and comment on their physiognomy, or to suggest assumptions of their moral character based on their facial features.

The middle leaf of the cartouche contains Utamaro’s commentary on the woman combing her hair. He writes that “She has a nice personal appearance and in all respects is a good type. In general her passions run deep, but she is no fool to let them run away with her.”[3] Next, the leftmost leaf of the cartouche is signed "Utamaro the Physiognomist" [觀想歌麿]. According to art historian Julie Nelson Davis, Utamaro-as-physiognomist “invoked the male gaze on another dimension of the subject of women…the problem of feminine character, behavior, and sexuality.”[4] Finally, the red outline around the cartouche, along with the mark in the lower right-hand corner of the print [籐], make clear that the publisher of Kami-suki was Yamashiroya Toemon.[5]

Although he began his career illustrating kyōka e-hon, or Japanese picture books, Utamaro earned his fame through his various bijin ōkubi-e, translated as “large-headed pictures of beautiful women.” These bijin ōkubi-e, or bijin-ga, became the most popular Japanese prints of the nineteenth century due largely to Utamaro’s stylization and distinctive use of the bust portrait in printmaking.[6] Bijin-ga portraits, and nishiki-e prints in general, employed the expertise of several artisans including a designer, woodblock carver, and printer in order to create an acceptable finished product. After the print was designed and inked, thousands of copies could be printed and subsequently distributed to the public. Many works from this period, such as Two Women by Kitagawa Kikumaro, demonstrate not only the prevalence of the bijin-ga trend pioneered by Utamaro, but also the popular nishiki-e woodblock techniques of nineteenth-century Japan.

Utamaro experimented with various printmaking techniques as a means to reveal subtle distinctions between differing social classes of women during his time. He often selected his subjects from the category of working women that included teahouse waitresses, courtesans, and prostitutes, types that contrasted starkly with the stereotyped and idealized images of women that had previously been the norm in Japanese art.[7] Although this image confirms the social pressures for women to maintain a desirable physical appearance, Utamaro’s focus on characters from everyday life allowed his prints to capture a more realistic Japanese woman, and therefore a more realistic Japan, than many prior subjects in Japanese art.

[1] British Museum staff.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Julie Nelson Davis. Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty. (Oahu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), p. 169.

[5] Gina Collia-Suzuki. The Complete Woodblock Prints of Kitagawa Utamaro. (Weston-Super-Mare: Nezu Press, 2009), 566. See Also: Shugo Asano; Timothy Clark. The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro. (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 235.

[6] Ibid, 14.

[7] Tadashi Kobayashi. Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. (Bunkyō: Kodansha International, 1997), 88.

Author: Alec Story - Spring 2018

Two other less obvious beauty standards are also present in this work. The first of these is the blackening of the figure’s teeth, known as ohaguro. This time-honored tradition not only protected against tooth decay but also allowed married women to signify their beauty, health, and aristocratic status. The second, lesser-known beauty standard depicted in Kami-suki is hikimayu, or the removal of natural eyebrows in favor of drawn-on reproductions, often performed in order to make the application of white makeup (known as oshiroi) more convenient.

Shifting one’s attention away from the female figure, one can see that in the upper left corner of the print is a three-leaved cartouche containing information on the work's publisher and artist, Kitagawa Utamaro. The furthest-right portion of the cartouche offers the series title in which Kami-suki is a portion, Ten Types in the Physiognomic Study of Women (fujin sogaku jittai [婦人相学拾躰]) which was created between 1801 and 1804.[1] This group of works is frequently discussed in comparison with two incomplete series designed by Utamaro between 1792 and 1793: Ten Types in the Physiognomic Study of Women (fujin sogaku juttai [婦人相学十躰]), and Ten Classes of Women's Physiognomy (fujo ninso juppo [婦女人相十品]) .[2] Through each of these series, Utamaro hoped to display a variety of female “types” and comment on their physiognomy, or to suggest assumptions of their moral character based on their facial features.

The middle leaf of the cartouche contains Utamaro’s commentary on the woman combing her hair. He writes that “She has a nice personal appearance and in all respects is a good type. In general her passions run deep, but she is no fool to let them run away with her.”[3] Next, the leftmost leaf of the cartouche is signed "Utamaro the Physiognomist" [觀想歌麿]. According to art historian Julie Nelson Davis, Utamaro-as-physiognomist “invoked the male gaze on another dimension of the subject of women…the problem of feminine character, behavior, and sexuality.”[4] Finally, the red outline around the cartouche, along with the mark in the lower right-hand corner of the print [籐], make clear that the publisher of Kami-suki was Yamashiroya Toemon.[5]

Although he began his career illustrating kyōka e-hon, or Japanese picture books, Utamaro earned his fame through his various bijin ōkubi-e, translated as “large-headed pictures of beautiful women.” These bijin ōkubi-e, or bijin-ga, became the most popular Japanese prints of the nineteenth century due largely to Utamaro’s stylization and distinctive use of the bust portrait in printmaking.[6] Bijin-ga portraits, and nishiki-e prints in general, employed the expertise of several artisans including a designer, woodblock carver, and printer in order to create an acceptable finished product. After the print was designed and inked, thousands of copies could be printed and subsequently distributed to the public. Many works from this period, such as Two Women by Kitagawa Kikumaro, demonstrate not only the prevalence of the bijin-ga trend pioneered by Utamaro, but also the popular nishiki-e woodblock techniques of nineteenth-century Japan.

Utamaro experimented with various printmaking techniques as a means to reveal subtle distinctions between differing social classes of women during his time. He often selected his subjects from the category of working women that included teahouse waitresses, courtesans, and prostitutes, types that contrasted starkly with the stereotyped and idealized images of women that had previously been the norm in Japanese art.[7] Although this image confirms the social pressures for women to maintain a desirable physical appearance, Utamaro’s focus on characters from everyday life allowed his prints to capture a more realistic Japanese woman, and therefore a more realistic Japan, than many prior subjects in Japanese art.

[1] British Museum staff.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Julie Nelson Davis. Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty. (Oahu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), p. 169.

[5] Gina Collia-Suzuki. The Complete Woodblock Prints of Kitagawa Utamaro. (Weston-Super-Mare: Nezu Press, 2009), 566. See Also: Shugo Asano; Timothy Clark. The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro. (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 235.

[6] Ibid, 14.

[7] Tadashi Kobayashi. Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. (Bunkyō: Kodansha International, 1997), 88.

Author: Alec Story - Spring 2018

Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806)

Kami-suki (Bijin Combing Her Hair) 1801-4

Color woodcut on paper

72.1.285

Tomikichiro Tokuriki (1902–2000)

Woman Combing Her Hair 1947

Color woodcut

Walter and Martha Leuba Collection, University Library System

Beauty rituals are a recurring theme in Japanese prints. Utamaro’s print (right) depicts several women’s fashions of the Edo period, including blackened teeth and the removal of natural eyebrows in favor of make-up.

Utamaro’s print comes from his Ten Types in the Physiognomic Study of Women, and identifies its imagined subject to be a “good type” based on her appearance. Tokuriki’s more modern print (left) depicts a real woman: the wife of the artist. (This is Not Ideal, Fall 2018)

In Collection

Gift of Tadao Takamigawa

This is not Ideal: Gender Myths and their Transformation. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh University Art Gallery. 2018. Exhibition catalogue. Published on the occasion of the student-curated exhibition This is not Ideal: Gender Myths and Their Transformation at the University Art Gallery, University of Pittsburgh, October 26-December 7, 2018. University Art Gallery. Frick Fine Arts Building, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA 15260 ISBN: 978-1-7329013-0-8

Please note that cataloging is ongoing and that some information may not be complete.